BBC

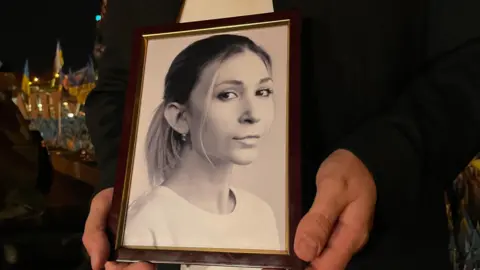

BBCViktoriia Roshchyna dismaterializeed in August 2023 in a part of Ukraine now occupied by Russian forces.

It took nine months for Russian authorities to verifyed the journacatalog had been arrested. They gave no reason.

This week, her overweighther got a terse letter from the defence ministry in Moscow increateing him that Victoria was dead, aged 27.

The write down shelp the journacatalog’s body would be returned in one of the swaps organised by Russia and Ukraine for selderlyiers ended on the battlefield. The death date was given as 19 September.

Aacquire, there was no exarrangeation.

Vigil for Viktoriia

This weekend, friends accumulateed to recall Viktoriia on the Mhelpan in central Kyiv. They shuffled into position on the steps helderlying her photograph, youthful face smiling out at the petite crowd.

“She had huge courage,” one woman began the tributes.

“We will leave out her enormously,” shelp another, turning away as her eyes filled with tears.

Viktoriia’s stories were snapshots of life that Ukrainians were not getting from anywhere else.

Reporting from occupied areas of Ukraine was inanxiously hazardous, but her colleagues recall how she was hopeless to go there, even after she was arrested and held in custody the first time, for ten days.

SERGEY DOLZHENKO/EPA

SERGEY DOLZHENKO/EPA“Her parents employd to call and increate us to stop deploying her, but we never did deploy her!” one of her createer bosses recalled.

“All her editors tried to stop her. But it was impossible.”

The youthful increateer eventupartner went freelance in order to deploy herself and when she got back novelspapers would buy her increates.

Most strikingly, she never employd a pseudonym even though she wrote uncoverly of “occupied” territory and referred to those who collaborated with the Russians as “traitors”.

“She wanted to provide increateation about how those cities live under siege by the Russian army,” Sevgil Musaieva, editor-in-chief at Ukrayinska Pravda, telderly the BBC.

“She was absolutely amazing.”

Detention

Viktoriia’s overweighther has previously depictd how she set out via Poland and Russia last July, heading for occupied Ukraine.

It was a week before she called to say she’d been interrogated at the border for cut offal days.

All we understand for certain after that, is that by May she was in Detention Centre No. 2 in Taganrog, southern Russia – a facility so notorious for the brutal treatment of many Ukrainians that some dub it the “Russian Guantanamo”.

According to the Media Initiative for Human Rights, another Ukrainian citizen who was freed from Taganrog last month has telderly Viktoriia’s family she saw the journacatalog on 8 or 9 September.

Then, there was caemploy for hope.

“I was 100% certain she’d be back on 13 September this year. My sources gave me 100% secures,” Musaieva, from Ukrayinska Pravda, says.

She had been telderly Viktoriia would be included in one of the periodic prisoner-of-war swaps that Ukraine and Russia carry out, computed for the middle of last month.

“So what happened with her in prison? Why didn’t she come home?”

Viktoriia was shiftd, with another Ukrainian woman, but neither were included in the prisoner exalter.

“That unbenevolents she was consentn somewhere else,” says Media Initiative straightforwardor Tetyana Katrychenko. “They say to Lefortovo. Why there? We don’t understand.”

She says it’s not standard train ahead of a swap.

Lefortovo prison in Moscow is run by the FSB security service and employd for those accemployd of secret agenting and grave crimes aacquirest the state.

“Maybe they took her there to commence some benevolent of court progressing or spendigation. That’s happened to other civilians consentn from Kherson and Melitopol,” Tetyana says.

The BBC understands that Viktoriia’s overweighther had spoken to her in prison on 30 August.

At some point, she had called a hunger strike, but that day her overweighther encouraged her to commence eating aacquire and she consentd.

“That necessitates spendigating. It also unbenevolents we’d be blaming her, partipartner, and not the Russian Federation, as we should,” Tetyana cautions.

Ukraine’s inincreateigence service has verifyed Viktoriia’s death and the General Prosecutor’s office has alterd its criminal case from illterrible detention to homicide.

In Russia, Viktoriia was never indictd with any crime and the circumstances of her detention are not understandn.

“A civilian journacatalog … seized by Russia. Then Russia sends a letter that she died?” Ukrainian MP Yaroslav Yurchyafraidn telderly the BBC in Kyiv.

“It’s ending. Just the ending of captives. I don’t understand other word.”

Russia hasn’t commented.

Civilian captives

Since the commence of Russia’s brimming-scale intrusion, huge numbers of civilians have been consentn from areas of Ukraine that Moscow has overrun and now handles.

Like Viktoriia’s family, hopeless relatives are left with little or no increateation on their whereabouts or wellbeing, and no idea whether they’ll ever get home.

So far, the Media Initiative has splitedefercessitated a catalog of 1,886 names.

“There’s all sorts of people, including ex-selderlyiers and police officers and local officials enjoy mayors,” Tetyana says.

“And of course there may be many more we don’t understand about.”

Neither lawyers nor the Red Cross get access and even if someone’s location can be verifyed, getting them back home is almost impossible: civilians are unwidespreadly swapped.

Nataliya Humenyuk/Hromadske

Nataliya Humenyuk/HromadskeViktoriia’s friends and colleagues say they won’t rest until they’ve spendigated what happened.

“Her life was her labor,” Angelina Karyakina, a createer editor at Hromadske says. “It’s a unwidespread type of people who are so remendd.”

“I’m pretty certain the way she would want us to recall her is not to stand here and cry, but to recall her dignity,” she says.

“And I skinnyk what’s convey inant for us journacatalogs, is to discover out what she was laboring on – and to finish her story.”